At the moment the two dominant influences on global share markets are the ongoing Covid pandemic and forecast rising interest rates. We don’t have any insight into how and when Covid will resolve itself but we have some pragmatic thoughts on interest rates and their impact on share markets.

Some Quick Scene-Setting

The particular interest rates we’re focusing on here are the rates paid on Government bonds. These are called “risk-free rates” because reputable governments are expected to always honour their debt obligations so there’s supposedly no risk in lending them your money. These risk-free rates, especially the interest rate on 5 to 10-year Government bonds, are one of the inputs into company valuations. All else being equal if these interest rates rise then share prices fall, and if these interest rates fall then share prices will rise.

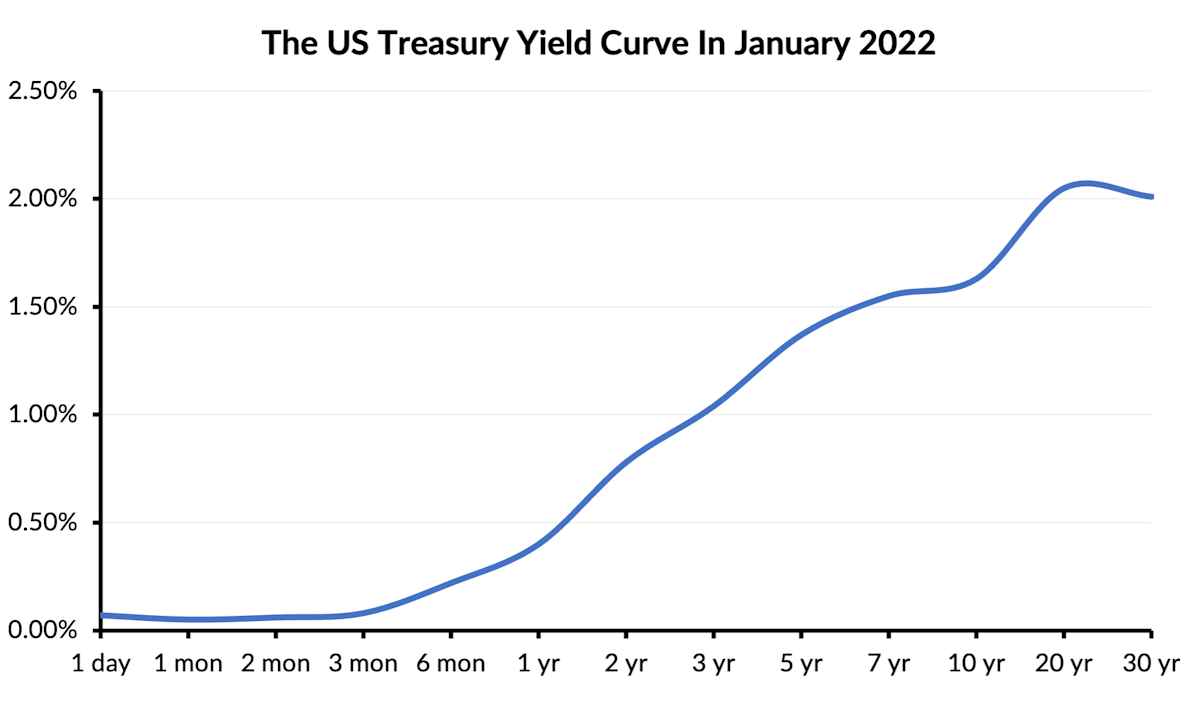

Central banks strongly influence interest rates through where they set the overnight cash rates (which in New Zealand we abbreviate to OCR). All interest rates, for borrowing and for investment, from private companies and from governments, anchor back to these central bank cash rates. This gives us what’s called the “yield curve”, which is the profile of how these interest rates change as the term of the debt gets longer. For example here’s the yield curve on US government bonds at the beginning of January 2022.

As the term, or duration, of the debt gets longer so the interest rate gets higher. That’s an important relationship we’ll come back to later.

The central banks primarily set the overnight cash rate in response to inflation. Typically a central bank is mandated to maintain inflation within a set range. For example the Reserve Bank of New Zealand is mandated to maintain inflation between 1% to 3% pa over the medium term (1).

Simplistically … when the central bank raises the overnight cash rate the longer-term rates also rise, in order to maintain the upwards slope of that yield curve. Those higher long-term rates in turn stifle economic activity. Borrowers (for example mortgage holders) face higher interest rates so have less discretionary income to spend. Companies face higher financing costs, so they tend to defer investments. And the currency rises, which is a headwind for exporters and makes imports relatively cheaper, both of which further weaken the local economy. The overall effect is to take excess heat out of the economy, which will temper inflation.

That’s not without cost. People feel poorer. The labour market gets hit because companies are less likely to take on new staff, and in fact are more likely to shed staff. Economic growth slows. This isn’t a surgical process – all aspects of the economy are hit, not just the over-heated parts. So it’s a crude-but-effective measure that has a lot of collateral damage. It’s somewhat like a doctor saying they’ll cure your fever by strangling you rather than giving you paracetamol.

And it’s not without risk. If the central bank overshoots and raises the overnight cash rate too high (over-strangles the patient) then the risk of an economic recession rises. That risk is heightened because there’s a lag between the central bank raising rates and the inflation ebbing. History suggests that lag often provokes central banks into over-tightening.

So Why Might Central Banks Raise Rates In 2022?

Mainly because inflation has risen markedly in the last twelve months, well above the levels in central bank mandates. That inflation has several drivers, including:

- Demand has rebounded from Covid faster than supply,

- This has been compounded by supply chain disruptions, which had been slowly resolving but are now re-occurring because of the number of people isolating from Omicron infections,

- Geopolitical tensions have significantly raised the cost of oil and natural gas,

- The pool of people available for work has reduced post-Covid … immigration is lower, some workers have voluntarily left the workforce, some workers are having to care for children locked-down from schools, and sadly some workers have died … so companies are having to compete harder for staff which is driving pay raises.

So central banks are eyeing their inflation mandates and preparing to raise interest rates. Note though that raising interest rates won’t magically unblock logistics chains, or resolve geopolitics, or whistle up a lot of new workers. But it will stifle demand to a lower level that the constrained industry and labour market can comfortably supply. They're strangling the patient.

Trading banks will also lobby for higher interest rates, because it gives them room to increase their Net Interest Margin (NIM), which is a bank’s main source of revenue. Trading banks’ self-interest is served by higher interest rates. In the last week JPMorgan in the US suggested the Federal Reserve might raise their cash rate by nearly 2% pa, and here in New Zealand the ANZ’s economists floated the idea that the OCR could reach 3% pa. They want higher interest rates because it's good for their business.

And central banks also won’t mind nudging cash rates higher because it then gives them room to lower them again in any future recession. At some point in the cycle the central banks need to re-load their stimulus guns, in preparation for the next crisis.

But Why Might Central Banks Not Raise Rates In 2022?

We think there’s two practical and one political reason why central banks might not raise rates as much as many commentators are forecasting.

Firstly, despite the recent inflation Covid is still with us and there are likely to be further disruptions to our economies in 2022. That suggests central banks should still err towards being stimulatory not punitive. Remember their inflation mandate is “over the medium term” – they can tolerate another six to twelve months of “wait and see” time while Covid (hopefully) properly clears.

Secondly, and importantly, because they will need to be cautious about inverting the yield curve. That’s when the interest rates on longer-term debt end up lower than the interest rates on shorter-term debt, so that yield curve chart we showed above would change to be flat or sloping downwards. An inverted yield curve is seen as the strongest predictor of an imminent economic recession.

Remember central banks can only change the overnight interest rate – the very left-hand end of that yield curve chart. That does influence the longer-term rates, but so do a lot of other factors. At the moment there’s still a lot of money looking for attractive investments and that wall of money puts a strong lid on the interest rates on longer-term (10 year and longer) bonds. With that heavy lid on long-term rates raising overnight rates aggressively could quickly invert the yield curve and set the scene for a recession.

Thirdly, because it’s politically expedient to run “hot” inflation at the moment. Covid has left governments owing significantly more debt. Those governments will be happy to inflate some of that debt burden away so will likely prefer inflation to remain at higher levels for a few years. Just don’t expect them to say that out loud.

On Balance What Do We Expect?

Firstly, we expect central banks to talk a big game. Plan A will be to threaten to raise rates, in the hope that will achieve some of the central banks’ objectives without them actually having to do anything. That’s exactly what we’re seeing already in the US – rates are rising before the Federal Reserve has really moved.

Secondly, we expect a few sharp interest rate rises through the first half of 2022. Central banks will want to try to dampen inflation early, before it becomes a repeating spiral. And they will want to be seen to have backed up their public statements. Two or three 0.25% pa rate rises will convey the message that they are taking this seriously, but will still leave rates at historically low levels and shouldn’t threaten the yield curve.

But, thirdly, we expect central banks to be cautious after the first few rate rises. We expect that rate rises in the second half of 2022 will rest heavily on whether Covid is truly behind us by that stage. To us talk of four or more rate rises through 2022 is rhetoric that would need a material improvement in the public health situation to come to pass.

We’ve been interested to see the equity markets panic over interest rate rises and stimulus wind-downs, but at the same time see the bond and foreign exchange markets remain relatively calm, and the price of classical inflation hedges like precious metals stay flat. To us that suggests the equity markets are over-reacting. Again.

We do expect to see interest rate rises through 2022, but even a 1% pa rise in overnight rates shouldn’t have an undue effect on the share price of companies that are growing their earnings at 15-20% pa and that have pricing power that allows them to pass on inflation and maintain their margins (2). Where we would expect to see a stronger impact would be in the share prices of “bond-like” companies such as utilities and commercial real estate, where the growth is lower and bonds are an easier substitute investment.

So if, through 2022, the companies the Fund invests in were to grow their earnings by 15-20% pa, but see their share prices only rise by 10% or so, then that wouldn’t surprise us. But at this point we don’t see the rationale for a collapse in their share prices because of inflation or interest rates.

- Note that there’s several different measures of inflation, and “medium term” is a little vague.

- For the corporate finance geeks … think back to the CAPM formulas for the cost of equity. If the 10-year risk-free rate rises by, say, 0.75% pa then yes all else being equal that will raise Ke, but not by very much. If Ke goes from, say, 9% pa to 9.75% pa then that will reduce the equity valuation, but not as significantly as the recent market movements would imply. (Yes, there’s also the forecast free cash-flows to consider, but that would take too long to really get into here).